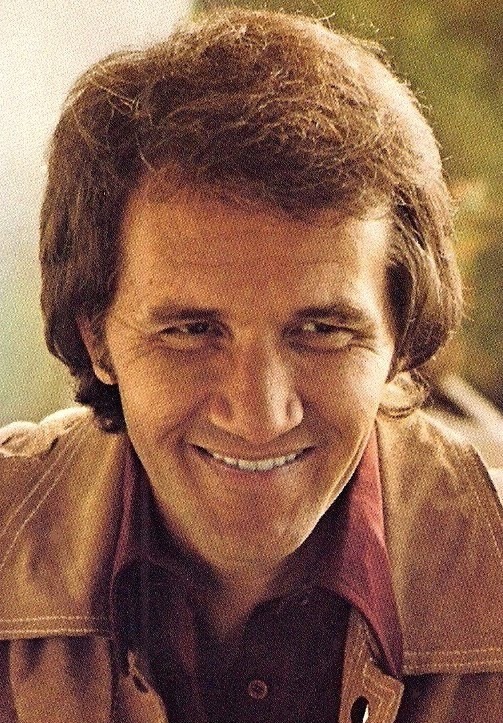

October 25, 1992 Roger Miller died of cancer at age 56

OCTOBER 25, 1992 – Grammy Award winning singer/songwriter/musician/actor **ROGER MILLER **(b January 2, 1936 in Fort Worth, Texas) died of cancer at age 56 at the Century City Hospital in Los Angeles.

It was in the fall of 1991 that Miller found out he had a form of lung cancer. His last performance was during CMA week in Nashville. Publicly, he refused to let his illness faze him. After a year of treatment and one remission. A week after his death, his wife Mary held a memorial service for him at a place he held so close to his heart, the Ryman Auditorium in Nashville. Mary wanted the memorial to be a celebration of his life. Hundreds of relatives and friends, many of whom had known him when he was still the Singing Bellhop, squeezed into the Ryman to tell their favorite Roger Miller story and listen again to his music. It was a beautiful tribute to the man Roger was, and to the unique artist represented by this career retrospective. For if his music proves anything about Roger Miller, it’s that God made him equal parts laughter and soul.

Miller was born the youngest of three boys. His father Jean Miller died at the age of 26 from spinal meningitis when Roger was only a year old. It was during the depression and Roger’s mother, Laudene Holt Miller, was in her early 20’s. As she was unable to provide for the boys, three of her late husband’s brothers came and took one of the boys to live with them. Roger moved in with Armelia and Elmer Miller on a farm outside Erick, Oklahoma.

It was a difficult childhood. Most days were spent in the cotton fields picking cotton or working the land, and Roger never really accepted the separation of his family. He was lonely and unhappy, but his mind took him to places he could only dream about. Walking three miles to his one-room school each day, he started composing songs, the first of which allegedly went a little something like this:* “There’s a picture on the wall, It’s the dearest of them all, Mother.”*

Roger, of course, painted a somewhat more humorous and inventive picture of his school days.* “The school I went to had 37 students,” *he once said, “me and 36 Indians. One time we had a school dance and it rained for 36 days straight. During recess we used to play cowboy and Indians and things got pretty wild from my standpoint.”

Nevertheless, Roger, who also liked to tell people that he* “even flunked school bus,” *did let his humorous guard down now and then to comment on the insecure loner he truly seems to have been as a child. “We were dirt poor,” he once explained. “What I’d do is sit around and get warm by crawling inside myself and make up stuff… I was one of those kids that never had much to say and when I did it was wrong. I always wanted attention, always was reaching and grabbing for attention.”

Roger was a dreamer and his heart was never in picking cotton. Most days his daddy would catch him daydreaming.* “It’s really a good thing that he made it in the music business ’cause he would have starved to death as a farmer,”* said entertainer Sheb Wooley (1921-2003), an Erick native who married Roger’s cousin, Melva Laure Miller.

Fifteen years older than Roger, Wooley’s career would lead him to Hollywood and the movies. One of Wooley’s biggest hits was “The Purple People Eater.” In those days, Wooley and little Roger would ride out *”fixin fences, chasing steers and talking about stardom,” *Wooley recalls. The two would listen to the Grand Ole Opry on Saturday nights and the Light Crust Doughboys on Fort Worth radio by day. Miller came to idolize Bob Wills and Hank Williams, but it was Wooley who taught Roger his first chords on guitar, bought him his first fiddle, and who represented the very real world of show business that Roger wanted so much for himself.

Eager to follow in Wooley’s long tall footsteps while he was still in high school, Roger started running away, knocking around from town to town through Texas and Oklahoma. He took whatever work he could find by day and haunted the honky-tonks by night. His drifting came to an abrupt halt when he stole a guitar in Texas and crossed the state line back into Oklahoma. He had so desperately wanted a guitar to write songs on and this seemed the only way to get one, since picking cotton would never earn him the kind of money he needed for a guitar.

Roger turned himself in the next day and rather than put him in jail they offered to let him join the Army. Although he was only 17, he chose to go into the service. He was eager to be going someplace else and before long he was shipped to Korea, where he drove a jeep and earned one of his favorite one-liners,* “My education was Korea, Clash of 52.”*

Roger was terribly homesick, but his world was growing larger. Towards the end of his tour with the Army, he was sent to Fort McPherson in Atlanta. Assigned to Special Services, he played fiddle in the Circle A Wranglers, a well-known service outfit previously started by PFC Faron Young.

After Roger’s discharge from the Army, he headed directly for Nashville to see Chet Atkins. He told Chet he was a songwriter and Chet asked him to play something. Seeing that Roger didn’t have a guitar, Chet offered his to him. Roger just couldn’t believe he was sitting in front of Chet Atkins and playing his guitar. He said, “I was so nervous, people thought I was wavin’.” Roger proceeded to sing in one key and play in another. Chet was kind about it but suggested he work on his songs a little more and come back.

Roger used to say, “I was everywhere at once.” He had an energy that was new to Nashville. Needing to work while he pursued his dream, Roger took a job as a bellhop at the Andrew Jackson Hotel. “It had more dignity than washing dishes,” he later said. Situated right in the thick of Nashville’s downtown music district, the Andrew Jackson gave him proximity to the small but vibrant Country scene. Roger soon became known as the “Singing Bellhop.” He would sing a song to anyone who would listen on the way up or down the elevator.

Roger’s first break finally came when he was hired to play fiddle in Minnie Pearl’s road band. His second break came when he met George Jones at the WSM radio station one night and played him some of his songs. Jones then introduced Roger to Don Pierce and Pappy Daily of Mercury-Starday Records and asked them to listen to some of the new kid’s material.

Auditioned at the Andrew Jackson, Roger impressed the Starday brass enough to be granted a session in Houston. George and Roger rode to Texas together and wrote some songs along the way. They co-authored “Tall, Tall Trees,” which Jones recorded in the spring of 1957 and “Happy Child” which Jimmy Dean recorded that same spring. Meanwhile, Roger cut some of his own songs, including the honky-tonk weeper, “My Pillow,” and “Poor Little John.” That October, they were paired on the first single of Roger Miller’s career.

The Mercury-Starday record went absolutely nowhere, but Roger continued to struggle away, writing for Starday and recording mail order sound-a-like records of other artists’ hits.

Married and with his first child, Alan, on the way, Roger considered getting out of the business entirely. He decided to move to Amarillo and join the fire department. He would work all day and into the night then go to the clubs and sing after work. There was little time for sleep. One of Roger’s band members was asked one time, “Does Roger ever sleep?” He replied,* “I don’t know, I’ve only been with him three years.” *Roger said there were only two fires while he was at the fire department. “The first was a chicken coop. I slept through the second one and they suggested that I seek other employment.”

Nevertheless, at a show in Amarillo, Roger met Ray Price and several months later, the superstar singer hired him to replace tour singer Van Howard in the Cherokee Cowboys.

With his wife, Barbara, Roger moved back to Nashville, bringing with him a new song called “Invitation to the Blues.” He somehow got the song to movie cowboy Rex Allen, who recorded it for Decca in early 1958. But when Allen’s version started to get hot, Roger suggested to his new boss that he cover it. Paired with “City Lights,” written by Bill Anderson, Price’s “Invitation to the Blues” became a #3 hit.

Meanwhile, before the Price record gave him full-fledged hit writer’s credentials, Roger had already signed a songwriting deal with Tree Publishing for an unprecedented $50 a week. Tree’s daily affairs were handled by Buddy Killen, an Opry bassist who met Roger at a downtown watering hole. They quickly began a life-long friendship.

With Killen plugging his songs, Roger started to score hits for other artists. Ernest Tubb took “Half a Mind” to #8 and Faron Young cracked the Top Ten with “That’s the Way I Feel.” Jim Reeves went all the way to #1 with Miller’s “Billy Bayou” and followed it a few months later with “Home” which rose to #2. Suddenly Miller was as hot as a hillbilly songwriter could be in the late 1950’s, but he was also proving himself to be the type of carefree spirit who gave industry players fits.

“Buddy had to jump-start Roger a lot to get him to write in those days,” said Bill Anderson, whom Roger brought to Tree in the wake of “City Lights.” “Roger would come in with seven lines or six lines of a song. It’d be something fabulous, and Buddy would just have to almost take him and chain him to the table to make him finish. Ernest Tubb wrote the last verse of ‘Half a Mind’ cause Buddy couldn’t get Roger to sit down and do it. Roger was the most talented, and least disciplined person that you could imagine. It was his personality. Roger was the closest thing to a genius I think I’ve ever known. The other side of that undisciplined genius was revealed through Roger’s propensity for giving away lines other writers would have killed to make up.” Says Andersen, “He’s the one that came up with the line in my song, ‘Po’ Folks’ – ‘If the wolf had ever come to our door, he’d have had to brought a picnic lunch.’ He wouldn’t let me put his name on the song.”

“The Songwriters in Nashville would follow him around and pick up his droppings,” added Killen, “because everything he said was a potential song. He spoke in songs.”

Much as songwriting and writers meant to him, Roger still wanted a career as an artist. To that end, Killen landed him a deal on Decca Records in 1958. In September that year, he cut a Decca duet with Donny Little, later known as Johnny Paycheck, that was more Paycheck than Miller. But three months later, they flip-flopped leads, with writer Paycheck singing uncredited harmony on Miller’s “A Man Like Me” b/w “The Wrong Kind of Girl.” Like his Mercury-Starday single, Miller’s first Decca sides were pure unadulterated honky-tonk. Yet like the Starday single, the Decca record flopped.

Roger’s second Decca single (not counting the initial Paycheck duet) was another matter. The A-side was Nashville country pop, but the far superior B-side, “Jason Fleming,” rocked. Recorded in June 1959, Miller’s ode to Paul Bunyan was the first of his songs to really hint at the manic music of which he was capable.

With his records sitting around and his writer’s royalties spent before he had earned them, Roger took road work where he could. Though he remained great friends with Ray Price, he hadn’t stayed long with the Cherokee Cowboys, in part because his harmony phrasing, which was as idiosyncratic as his wordplay, drove Price nuts.

One night while Roger was sitting out back of Tootsie’s, feeling really down and out, Faron Young came by and said,* “What’s the matter with you boy?” *Roger told him he didn’t have a job. As Roger later reveals, Young recognized his plight and asked him, “Are you a drummer?” Roger said, “No, but when do you need one?” Young said, “Monday,” and Roger said, *”Monday, I’m a drummer.” *Young sent him down to Shobud to get a set of drums and he was Faron’s drummer for a year or so. During that time, Young recorded “A World So Full of Love.” Also, dating from this year with Young is a rare Armed Forces Radio version of “When a House is Not a Home” which Roger had given to Little Jimmy Dickens.

While still drumming for Faron, Roger signed a deal with RCA’s Nashville office, which was run by guitar legend Chet Atkins. It had been many years since Roger’s first meeting with Chet. As a producer Atkins had played a major role in defining the soft-edged country style that was coming to be known as the Nashville Sound. At the time, RCA’s biggest Country act was Jim Reeves, and his success with Roger’s songs probably had a lot to do with making the deal. When Killen brought Atkins a new tune of Roger’s called “You Don’t Want My Love”, he suggested that Atkins let Roger cut it himself. Atkins agreed. On August 10, 1960 Roger recorded “You Don’t Want My Love” (later and better known as “In the Summertime”) at his first RCA session.

Atkins showed admirable faith in Miller’s scatted vocals and ad-libbed blues tags. The record took off, however, and was quickly accepted as Roger noted at the time “by the multitude.” It reached #14 on the Country charts and was covered in the Pop field by Andy Williams. All told, the record gave Roger sufficient star clout to hit the road as a solo act.

Less than a year later, Roger broke into the Top Ten for the first time with “When Two Worlds Collide,” which he and Anderson had written by the light of the moon in the back seat of Roger’s Rambler station wagon enroute to Texas. A fan of the sci-fi classic film “When Worlds Collide” (1951), Roger had been wanting to write a song by that title for years. Peaking at #6 “When Two World’s Collide” proved to be the high point of Roger’s RCA career.

Another release was “Lock, Stock and Teardrops,” a marvelous Miller ballad later revived by K.D. Lang. Like his songwriting success of the late 1950’s Roger’s artistic success on RCA proved a deceptive measure of his career advancement. His royalties were eaten up by advances from Tree, and gigs paid in the $150-$225 range. His first marriage, which had given him three children, was falling apart as well, and his extracurricular habits had already earned him a reputation as Nashville’s “Wild Child.” By November 1963, Miller had been dropped by RCA and was about as broke down and disgusted as a singer-songwriter could ever be.

For Roger, who by then had every reason to doubt that Country music could make him a decent living, the one ray of hope was in the glow of the television spotlight. A natural comedian, he had made a considerable splash when his old friend Jimmy Dean, guest hosting on “The Tonight Show,” invited him on the program one night in 1962. Roger’s walk-on was a hit. His show-stopper was a rendition of “I Walk the Line” that Roger sang as, “I hold my pants up with a piece of twine.”

Appearances on other shows followed and by the end of 1963, Roger had begun to think he might have a better shot at stardom on the TV screen than on the roadhouse jukebox. He wanted to head to California and take up acting. His only problem was figuring out how to finance the move.

Long about the time Roger was having success on TV, Smash Records, an upstart subsidiary of Mercury Records, was taking pop radio by storm. Headed by Charles Fach, Smash went into business in February 1961 and in less than three years’ time had already scored such monster hits as Bruce Channel’s “Hey Baby” and the Angels’ “My Boyfriend’s Back.” Confident and eager to expand, in 1963 the label signed Jerry Lee Lewis and James Brown and, in Nashville, Roger Miller.

As Fach recalls, he and Mercury executive Lou Green came to Nashville that November to attend the annual disc jockey convention. The two of them and Shelby Singleton, head of Mercury in Nashville, were having dinner at the steakhouse in Printer’s Alley, a popular downtown night club strip, when Roger walked in with Buddy Killen. According to Fach, who confirms that it was Roger’s “Tonight Show” appearance that first caught his attention, Singleton said to him, “There’s Roger Miller. He’s just been dropped by RCA. Why don’t we pick him up for Smash? Shelby went over and talked to Buddy for thirty or forty seconds, and came back and said, ‘We got a deal.'”

Roger was still planning on moving to California and the Smash deal was his way out.* “Roger came in and asked if there was anyway we could give him sixteen hundred dollars. He would really appreciate it.”* Fach, after thinking it over, agreed to pay, but with the understanding that Roger would record sixteen sides at a rate of $100 per side. From these cuts a single and an album were to be released.

With Kennedy producing, Roger went into Music Row’s famous Quonset Hut Studio for the first Smash session the night of January 10, 1964. With Bill Justis handling the arrangements, Roger cut a trio of full production numbers that night, opening with the rich country soul of “Ain’t That Fine,” written by Dorsey Burnette. He followed with a song called “Why,” then closed out the session in the early morning hours with one of his own originals, a moody song called “Less and Less”, that Kennedy gave the Nashville Sound treatment.

The latter was a beautifully orchestrated performance – lush, but not overbearing – and Kennedy pegged it as the A-side of Roger’s first Smash single. After only a few hours of sleep, at ten o’clock in the morning of January 11th, Miller and Kennedy and a small combo of Music Row pickers returned to the studio to record the album sides and earn Roger the rest of his moving money.

Roger brought twelve of his own songs with him, and Kennedy made sure that everyone understood the album agenda was totally different from the single session the night before. The accompaniment was to be sparse. It was Roger, Ray Ederton and Harold Bradley on guitars, Hargus “Pig” Robbins on piano, Bob Moore on bass, and Buddy Harman on drums. With the tape rolling the tiny group kicked in and Roger leaned into the unforgettable lyric of that winter day’s first song.

Clocking in at just over two unique minutes, “Chug-a-Lug” set the tone for what turned out to be one of the most important days in the history of Country music. Miller, Kennedy, and the band “hit the groove that really felt right,” as Kennedy put it, and stayed in the groove through all twelve sides. Roger wound up cutting fifteen, not sixteen songs during the two day run. The session was as off-the-cuff as they come, but it was organized in such a loose fashion as to let Roger, the complete artist, finally take over. “I was just conscious of letting Roger and his music shine,” said Kennedy.* “That was the goal, and I think we accomplished it.”*

Of all the songs cut that day, “Dang Me” stood out over the rest. Roger wrote it in four minutes in a Phoenix hotel room while picturing himself sitting in a booth at Tootsie’s Orchid Lounge, the legendary musicians’ hangout. Ironically, Kennedy very nearly missed the chance to release “Dang Me” upon an unsuspecting public. Each night he would take home tapes from the session that he had produced that day, but the Wollensat recorder he played them on at home didn’t have a full-size take-up reel. So the reel filled up before it got to “Dang Me.” Kennedy had already started “Less and Less” through the singles pipeline when he finally bought a full size take-up reel and played the rest of Roger’s session.* “My kids came screaming down the stairs when ‘Dang Me’ came on,” he says. “They thought that was the greatest thing they’d ever heard. I started playing it over and over and over again, and I said, ‘What have I done?'”*

Kennedy was now certain “Dang Me” was the hit, so he called Mercury. He explained he had to scrap “Less and Less” as the single. They agreed to slot “Dang Me” as Roger’s first Smash single. The original version of “Less and Less” was sent to the vault where it remained until a couple of years ago.

Meanwhile, Roger pocketed his session stash and* “caught the 3:44 pm covered wagon for California.”* There he moved into an apartment above pop luminary Lee Hazelwood’s garage.

“Dang Me” had a lot to compete with. The British Invasion was in full swing. Nevertheless, “Dang Me” was such an original, infectious song, it broke huge right out of the box. The action hit first in Seattle and Houston on pop radio, then on jukeboxes everywhere.

Mercury was hoping for some Country success, but they were pleasantly surprised that it was more than that. In fact, Smash Records had no Country promotion department, but that probably worked to Miller’s advantage with the Top Forty deejays, who associated the Smash label with notoriety and runaway pop success. As for the Country deejays, they’d known Roger for years anyway. By the end of June, “Dang Me” was flying up both charts simultaneously. “The hit charts look good with ‘Dang Me,'” Miller acknowledged at the time, “very American.”

With his career taking off, Roger got out of Lee Hazelwood’s garage and hit the road.* “The day ‘Dang Me’ was released, I played a little club in northern California for seventy-five dollars,”* Miller told William Whitwood. “Had four people in the audience and got a hot check. But in about a week my phone started ringing. Wanting to do this and that, and pictures, and busy, busy, busy. After that, uh, I don’t know what became of me after that.”

Early that summer, Miller worked a San Francisco TV show, allegedly “breaking all audience reaction records,” and in June he embarked on a ten-day “TV-deejay tour of the Midwest.” On August 11, he stopped off in Nashville long enough to record “Re-incarnation” and “Hard Headed Me,” a couple of his goofiest songs yet, and during July or August he sat in front of the Smash microphones at three separate locations in the South for live recordings.

By September, “Dang Me” had about run its course, at least on Top Forty radio (it spent twenty-five weeks on the Country charts); but no matter, for “Chug-a-Lug” was already hitting hard and fast. Concerned about offending their core Country audience, Roger and Kennedy had initially balked at releasing “Chug-a-Lug” as a single, and at one point an alternate version of the song was produced with the word “wine” edited out. But Fach, seeing the larger picture, knew that Miller’s ode to forbidden liquid pleasures would be a monster. “Charles was the one who wanted ‘Chug-a-Lug,'” said Kennedy. “We didn’t know he was testing this thing in places,” he said,* “The college crowd is eating up this ‘Chug-a-Lug’. And I said, ‘Well, we’ve got our country fans to consider here. And fortunately they loved it too.’”*

Recorded in October, “Do Wacka Do,” a lesser hit but one of Miller’s most enduring lyric inventions, followed “Chug-a-Lug.” Then, on November 3rd during yet another album session, Miller recorded “King of the Road,” his career record.

Roger had written the song that summer, probably during a Midwest TV tour in June. As he often told the story, he was on the road somewhere outside Chicago when he saw a sign that read “Trailers for Sale or Rent.” He wrote the first verse, but got no further. In Boise, Idaho, to “induce labor,” as he put it, he saw a hobo in an airport gift shop. It was the inspiration for the rest of the song. The scribbling of “King of the Road” now hangs in a shadow-box at the Roger Miller Museum in Erick, Oklahoma. All told, “King of the Road” took him six weeks to write, as opposed to the four minutes he spent on “Dang Me.”

Released early in 1965, “King of the Road” (featuring Buddy Killen and guitarist Thumbs Carlisle on finger snaps) took off as fast as “Dang Me” had, so fast that Kennedy didn’t even know it was happening until Fach called him one morning and said, “That hobo song’s a smash.” The hobo song was #1 on the Country chart in March and stayed there for five weeks. It got to #4 on the Pop chart, and in May the single was certified Gold for sales of a million copies.

Not that anyone had forgotten “Dang Me,” for on April 13th, at the Carousel Club in Nashville, Miller was awarded his first five Grammy’s including, hilariously, the award for “Best New Country and Western Artist.” He repeatedly called Kennedy to the microphone to share in the credit for his phenomenal success.

By the summer of ’65, Roger’s career was made. The first royalty check he received from Tree was for $160,000. *”He cried,” *Killen said. His persona was also well established. He was a breath of fresh air firing off one-liners and juicing prime time radio with his unique songs.

Roger’s inroads into the larger world of pop excited a flurry of articles in the mainstream press. Life magazine called him a “cracker-barrel philosopher”; in Time he was the* “unhokey Okey.”* In February 1966, Roger made the cover of the Saturday Evening Post for a hefty piece on the “Big Boom In Country Music,” and a couple of years later the New Yorker caught up with him in Las Vegas. In general, journalists trailed him for his quotes – his seemingly inexhaustible store of free association witticism and his extemporaneous observations. After all, who could resist a chart-topping hillbilly who called his music “depressive jazz”?

Roger, however, was never comfortable being portrayed as the down home court jester of pop.* “I don’t want to appear the hick,” *he said. “That’s the thing I fight a lot.” Proving his point, he continued to write and record terrific, serious music that showed many other sides of his personality.

For one thing, part of Roger’s genius was his ability to deliver essentially downbeat material like “Dang Me” in an upbeat manner that made the emotions involved seem much more complex. Destitution never sounded so appealing as in “King of the Road,” and abandonment never swung so freely as in “Engine Engine #9.” Thus, whenever Roger tackled a straight-ahead country sad song such as “Husbands and Wives” or “The Last Word in Lonesome Me,” the results were that much more effective.

Among the novelty smashes and lonesome ballads of Roger’s peak years were any number of hits like “England Swings” or “Walkin’ in the Sunshine” – songs the sole purpose of which had been to communicate his boundless joy in life.

Roger’s style rarely strayed from the tight,compact sound laid down on his first session. He used the same five musicians for the first five years or so. Occasionally a ringer or two would be brought in – Boots Randolph played the trombone part on “Kansas City Star,” and “My Uncle Used to Love Me but She Died” was recorded in Los Angeles with LA session players. Eventually, guitarist Chip Young was brought into the fold, and if an extra lick of some kind was needed, Kennedy himself would sit in.

By the end of 1966, Roger was in danger of becoming over-exposed. In September that year, hot off of appearances on Andy Williams’ TV show, Roger was given his own NBC program. Having other people writing his material and setting his routines was difficult for him. He had an impressive list of guests, but the show was cancelled after thirteen weeks.

Roger didn’t want anyone else using his train set so he blew up the train on the final episode. “It set my career back two years,” he later said. “It must have set the network back ten years.”

Charting early in 1967, “Walkin’ in the Sunshine” was Roger’s last crossover hit of his own writing. Later that year, he recorded but didn’t write the soundtrack for the western, Waterhole #3, and in October he finally cut “Old Toy Trains” which he had written two years earlier for his son, Roger Dean Miller, Jr.

Kennedy and Miller had good ears for interesting songs from other sources. People like Kris Kristofferson, Mickey Newberry, and Dennis Linde had come to them. In 1967, Roger scored what proved to be his last Top Ten hit with Bobby Russell’s “Little Green Apples.” Most people thought Roger had written it.

Just over a year later, Roger recorded “Me and Bobbie McGee” even as Kristofferson was writing it. Said Kennedy,* “We would go into the studio and cut, and I think Kris came in with some of the second verse. We loved what we were hearing with the first verse and the chorus… then I think while we were in the studio he brought in the lyric for the second verse.”*

In June 1970, with his songwriting still on hold, Roger finally got around to creating an album that he had been talking about for years. Called “A Trip in the Country”, it consisted of Roger singing a bunch of his old standards with straight-up honky-tonk arrangements. That was his roots. There were vintage songs like “Invitation to the Blues,” “Tall, Tall Trees,” “That’s the Way I Feel” and “Half a Mind”. He also slipped in “Don’t We All Have the Right,” which he had written in 1962 and which years later became a #1 hit for Ricky Van Shelton.

Mercury folded the Smash subsidiary in 1970, a move that spooked the superstitious artists on the label, including Roger. His recording dates grew sporadic, and the hit singles all but disappeared. His last chart record for Mercury was “Hoppy’s Gone” a song in which the death of a matinee idol, Hopalong Cassidy, virtually signifies the end of all that was just and true in America.

After leaving Mercury, Roger signed with Columbia Records. His first album for the new label was called, significantly, “Dear Folks: Sorry I Haven’t Written Lately,” though he then had begun to do so again. In fact, the best cut on the album, was “What Would My Mama Say.” In 1974, he wrote and sang songs for the Disney cartoon, “Robin Hood.” He also continued to work the road, never allowing his show to get stale.

“He was truly original, and he would just add on something that we had no idea what he was doing,” laughs Mary Miller, Roger’s third wife. Formerly a member of Kenny Rogers and the First Edition, Mary worked with her husband as a back-up vocalist from the 1970’s on.* “I always joked that the first year I knew him, I didn’t understand anything he said. He had a brilliant mind and a wonderful slant on things. There was such a richness to his life.”*

In 1981, Roger got a call from Willie Nelson who had been recording a series of duet albums with old friends like Ray Price. When Willie asked Roger, he said,* “Well, Will, you’ve done a duet with about everyone.”* Willie replied,* “I know, but we’re down to the M’s.”* Roger agreed and offered a new song, “Old Friends,” which he had written for his mama and dad back in Oklahoma, and of which he was especially proud. Ray Price joined them for the session, and the sweetly melancholy tune made a respectable showing on the charts. As it turned out, “Old Friends” was the last most people heard of Roger Miller until “Huck Finn” floated down Broadway.

The story of “Big River” is as fantastic as any of Roger’s life. The key man was Rocco Landesman, a former Yale professor at the Yale School of Drama who happened to be the world’s #1 Roger Miller fan.

*”I thought he was an absolute genius,” *Landesman said. On the way to a New York appearance by Roger at the Lone Star Cafe, Landesman conceived the notion that Miller ought to write a Broadway score – and “The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn” would be the perfect vehicle. He approached Roger’s wife, Mary, after the show. She encouraged him to write a letter to Roger with the idea. Roger jokes, “He made me an offer I couldn’t understand.”

Nevertheless, Landesman wrote a number of letters to Miller and about a year later had him convinced he was the right man for the project. Roger was off on another new journey. Landesman commissioned William Hauptman to adapt Twain’s book and the project was underway.

Roger, initially intimidated, spent a year and a half on the first phase of the musical. He was “*writing from every corner of my heart,” *as he put it. The pay opened at Harvard’s American Repertory Theater, then moved to La Jolla, California, where a struggling young actor named John Goodman took the role of Huck’s father, Pap. In the play, Pap’s feature song is “Guv’ment” which Roger wrote while thinking about the uncle who raised him. Elmer Miller didn’t drink like Pap, but he did *”used to cuss out the government,” *Roger said.

“Big River” opened at New York’s Eugene O’Neill Theatre on April 25, 1985, during one of the bleakest seasons in the history of the Great White Way. The press offered the hope, which they clearly considered him, that “Big River” might save the day.

As it turned out, the play was a smash hit, earning seven Tony Awards, including Miller’s for best score. When Goodman left the role for the movies, Roger took over his part for three months. He also made an album on MCA, called Roger Miller, on which he sang several songs from the play, including “Guv’ment” and the magnificent “River in the Rain.”

For Roger, Big River was the crowning achievement of a fantastic career that to him only then seemed complete. He is still the only Country artist to win a Tony Award. With Big River a proven success, Roger was able to relax at his Santa Fe home and focus on the family life he had made with Mary and their two young children, Taylor and Adam. “I (had) a brother who’s five and sister (who was) seven,” said Dean Miller, “and they were his all-consuming passion.” Roger had found a happiness with Mary and the children he had longed for all his life.

In September 1990, at the urging of Stan Moress, Roger’s longtime friend and manager, and booking agent Tony Conway, Roger embarked on a tour unlike any he had ever done – solo with guitar. Scared to death the first date, he slew the audience for ninety minutes.* “They laughed, they laughed, and they laughed,”* Conway said.

In 1995, Miller was posthumously inducted into the Country Music Hall of Fame. “This would have been his ultimate dream come true,” said Mary Miller, “the ultimate recognition of his songwriting and musical artistry.” When asked how Roger wanted to be remembered, he replied. “I just don’t want to be forgotten.”

SOURCES